Reissue: Formal clothes

Morning Dress

This piece is one I wrote back when I first started this newsletter in 2020. It is the first of a three-part series I did on formal wear and dress codes. Since I originally published it on Ghost, most of Oxford Dawn’s new members won’t have seen it, which is why I’m republishing it today.

November 2025 update: I’ve dragged this piece out of the archives at the suggestion of a loyal reader who expressed interest in the etiquette around formal dress. The topic is apropos to the holiday season since this is a time of year when many people have formal events that aren’t held the rest of the year.

Here I am in my half blue blazer. To obtain one, aside from winning a half blue, one must go to Walter's of Oxford, be fitted for it, and then wait six weeks. Their customer service is lovely, though, and they make the experience delightful. Absolutely no one knows where the blazer came from, but there are three plausible stories: 1) in the 1820s, the Lady Margaret rowing team at St John's College, Cambridge, wanted an informal jacket for warmth and comfort while training; 2) in 1837, the captain of HMS Blazer dressed his crew in striped jackets in preparation for receiving a young Queen Victoria; 3) they evolved from jackets worn by members of private clubs in the mid-nineteenth century. The blazer is the lowest rung of informality officially allowed by the university.

A blazer is more formal than a sport coat, but not as formal as a lounge suit, which is still informal daywear. It may be a surprise to some readers that the lounge suit, i.e. a two- or three-piece suit, is classified as informal dress. As such, it is not appropriate to wear to formal events during the day. There are a few exceptions, one of which is Oxford University academic events where gowns can be worn over lounge suits. This is because the academic gown, already held as formalwear, is considered the top layer – at such events gowns are never removed – and therefore a person isn't supposed to wear anything that could pull attention away from the gown.

In general, formalwear is divisible into morning dress – appropriate from rising until about 6:00 PM – and evening dress, to be worn from 6:00 PM until dawn. Each of these has subdivisions. When one says morning dress, one normally means a morning suit.

A morning suit comprises trousers, shirt, tie (in the most formal of circumstances only a cravat is allowed as the tie), waistcoat, tailcoat, black shoes, and top hat. The top hat is increasingly dispensed with but the rule is: top hat or no hat at all. It used to be that men regardless of age would also carry a walking stick. That is now dispensed with except for events such as Royal Ascot, where the stick serves a practical function – a man is supposed to use his stick to tap discreetly ahead of where he is walking to avoid stepping in mud. Dispensing with walking sticks at events is partly cost efficient, but it also because the walking stick is analogous to a sword from back in the days, e.g. ancien régime France, when men, regardless of rank, were expected to wear a sword as part of formal dress. As a result, men would not carry a walking stick into a sacred place, such as a church or synagogue, because of the rule against bearing arms into those places. (Obviously walking sticks are distinct from canes in this context.) This is one reason why one doesn't see men carrying walking sticks at royal weddings, which is where the general public customarily sees morning dress.

Morning suits have some aesthetic or social rules governing pairings and presentation. Morning coats come in dark blue, black, charcoal grey, or light grey. The light grey colour is only for warm months. The UK doesn't have the US's easy rule of ‘dark after Labor Day, light after Easter’. But there's about an equivalent time period: normally light coloured jackets from April through September, but dark coloured ones from October through March. While it is correct to wear either a wing- or turn-down collar as part of a morning suit, if a person chooses a wing-collar, then he may only wear a dark tailcoat, not a light grey one. The turn-down collar goes with either dark or light colours.

The waistcoat and coat are a set in the sense that the waistcoat should be visible above and below the tailcoat when it is fastened, but too much or too little of the waistcoat is a faux pas. The waistcoat must cover the waistband. It's customary for men to wear suspenders, rather than belts as part of morning dress. Most morning suit trousers won't have belt loops. I'll double back to this in an issue about formalwear accessories, but it is extremely gauche for a man's suspenders (UK: braces) to be visible. They are classified as undergarments and as such are held to the same rule: no showing!

Black shoes are required even if the suit coat is dark blue. This is because of the old rule ‘never wear brown in town’. As a clothing colour, brown is associated with informal, rural activities, such as fishing or shooting, so it's inappropriate to wear it, either in coat or shoe form, in urban environments or to formal events — even those in the countryside, such as Royal Ascot. As a result, even if a person is wearing a blue suit or trousers, if one is in such an environment, one is supposed to wear black shoes. This rule applies to women as well as men as far as brown shoes or coats are concerned. They may wear shoes in other colours, though, while men may only wear black shoes.

In this photo, the Dukes of Cambridge and Sussex are both wearing blue lounge suits, but only William has correct footwear. As a side note, this is one way militaries and law enforcement obtain a crisp look for their dress uniforms. If one looks carefully at officers in full dress blue, one sees that they are wearing black shoes with their dress trousers. Even Oxford enforces this rule: at my matriculation, a couple of young men wore brown shoes instead of the black ones we were all specifically told to wear. Porters took them out of line and they weren't allowed to enter the Sheldonian for the matriculation ceremony. People wearing white socks or no tights (US English: hose) were also taken out of line. The porters had a supply of black knee socks for girls who needed them, but any boys not in appropriate dress had to wait outside until the ceremony finished.

The following rule is entirely social: it is rather vulgar for groomsmen to wear matching morning dress at a formal wedding. This rule stems from the Victorian era when clothing hire companies realized they could market matching outfits (which themselves were probably products of bulk orders) to lower-class men who wanted to wear formal clothes at their weddings.

As a result, matching outfits signaled that the people involved had hired their clothes; in other words, they didn't own their own, which in turn meant they didn't come from backgrounds or work in professions where they wore such clothes organically. In truth, because of the origins of this rule, any matching among groomsmen's outfits is tawdry, even if they aren't wearing morning dress. Nowadays, the objection to matching is that it is counterproductive to individuality. A man is supposed to wear his morning suit in the colours that become him, and it's ungracious to force him to wear something different.

An important note: due to the fact that many European and East Asian men first encounter morning dress as a school uniform or professional dress code, there is a tendency for such men to show up in similar coloured waistcoats, ties, or coats as a result of institutional requirements. This is not considered matching as there is plenty of room for variation in style or fit.

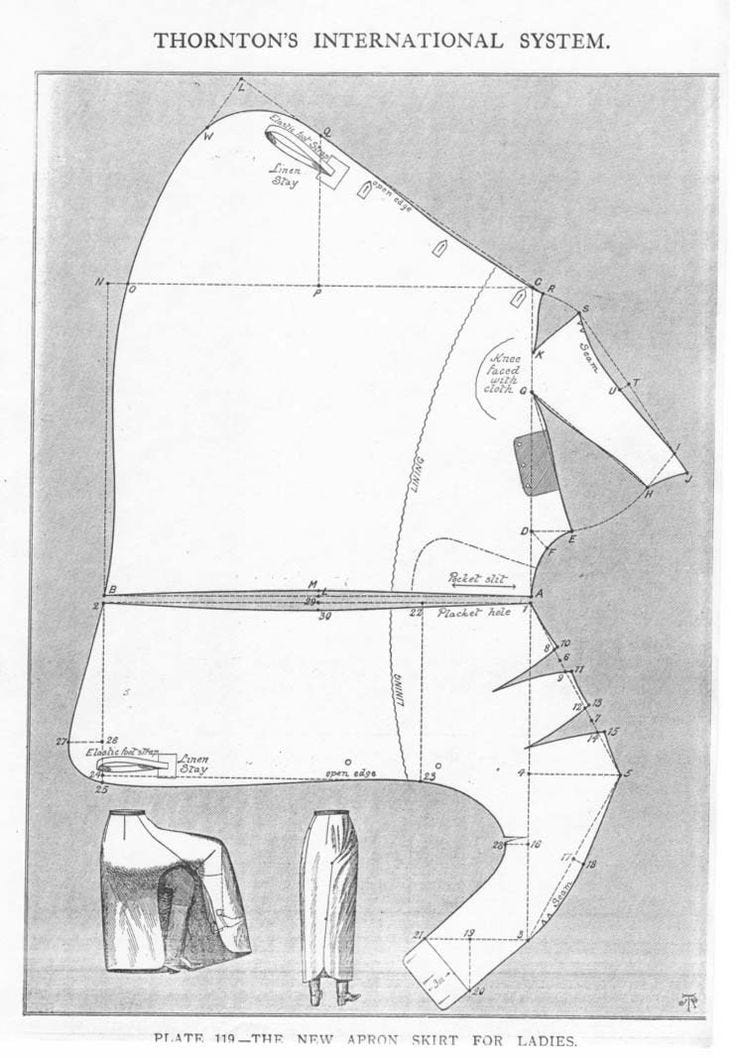

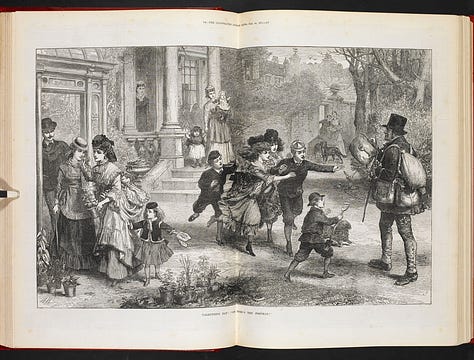

In modern times, women have a more difficult time with morning dress codes because a woman's equivalent never completely developed back when these codes organically evolved. This was not due to sexism or discrimination but reflects the outfit's original purpose. The morning suit began as a riding habit. The slit in the tailcoat allowed a rider to sit down in the saddle without sitting on his coat and potentially causing his head and shoulders to snap back. The waistcoat provided warmth while allowing movement at the waist, which is probably a reason belts aren't worn with morning dress. The top hat was originally protective gear. Older top hats were heavier than modern ones because they were made out of felt-covered wood which hypothetically protected the wearer's head in the event of a fall or if a horse bolted and ran under a tree branch. As a result of the outfit's practical, utilitarian purpose, women wore the same clothes, including trousers, with the addition of a side-saddle apron. The apron was a false skirt that fastened to the rider's ankle when mounted but could be fastened together in back when a woman was standing so that she appeared to be wearing a skirt.

This apron is the solution to the "puzzle" in Downton Abbey when Lady Mary is seen riding side saddle after her maid Anna spent most of an episode looking for "her ladyship's breeches," which had wound up in Lord Grantham's wardrobe by accident. (Did anyone else wonder that the servants didn't notice that one pair of trousers was significantly smaller than the others before putting said pair in his lordship's wardrobe?)

As the reader can see, it was socially permissible for a woman to decorate her top hat in a way men were not allowed to do. But at its core, the top hat was a unisex item. Because of its function as protective headgear, the top hat is unreliable as a class signifier for the nineteenth and some of the twentieth century.

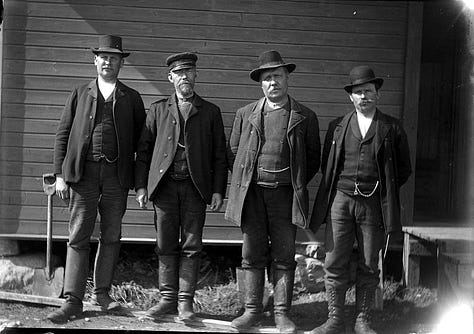

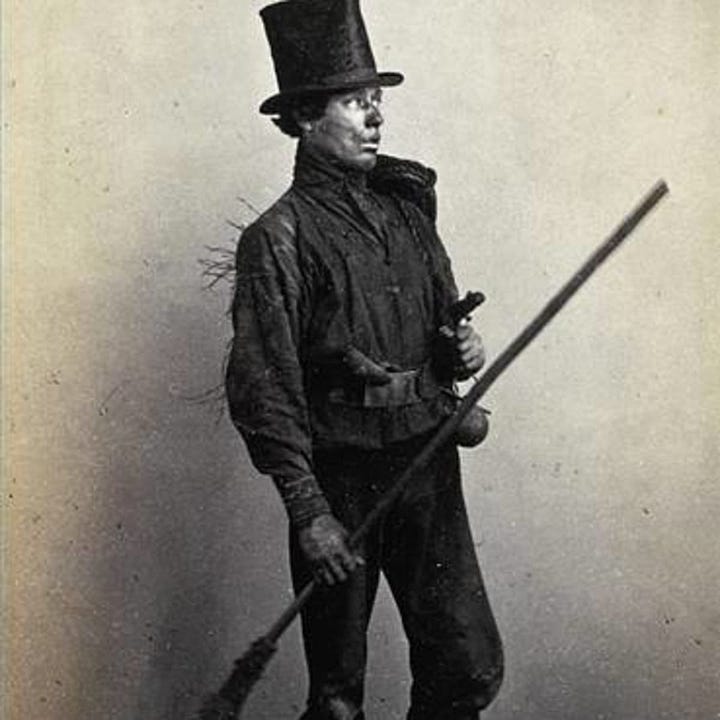

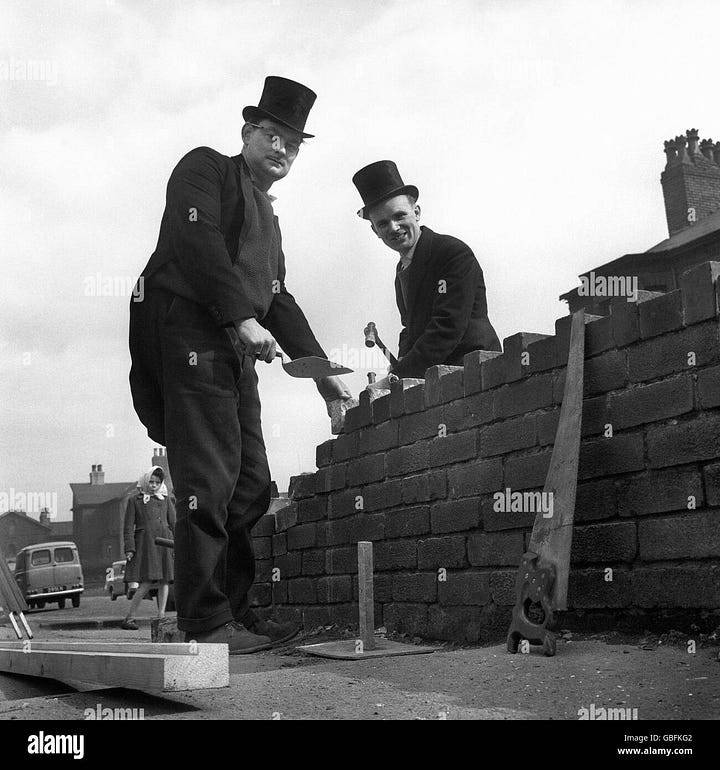

In the picture of laborers in Sweden in the early twentieth century, the man on the far left is wearing a top hat. The coachman, probably a Hansom cab driver, is wearing one in the center photo, but the man getting into the carriage is wearing a high-crowned bowler hat. And the postman in the print is wearing a top hat. Rather famously, chimney sweeps wore top hats, which became a cultural trope through books like Mary Poppins. While chimney sweeps (which is still a proper trade in Europe) occasionally still wear top hats in the name of tradition, the practice probably had its origins in the fact that the hat was the period equivalent of a hard hat.

By the late nineteenth century, chimney sweeps routinely wore tailcoats as part of their work uniform. The custom probably began as a practicality – black coats didn't show soot – but became a tradition. The bottom right picture was taken in 1962, and it shows two bricklayers in Manchester. While their formal clothes might have been a marketing gimmick since the description noted that they ran a builder's business, these photos help explain why the Victorians held renting formal clothes to be so egregious: if cab drivers, postmen, bricklayers, or chimney sweeps wore clothing suitable for formal occasions (even if in need of cleaning or mending), was a man unemployed, was that why he had no need for formal clothes (a simplistic view but one in character to the time period, e.g. Somerset Maugham's Liza of Lambeth)?

The top hat as an elite symbol is rooted in the fact that it was a part of the school uniform for British private preparatory boarding schools, most notably Eton and Harrow, where boys would become accustomed to wearing formal clothes on a daily basis.

The photo on the left is the infamous "Toughs and toffs" photo from 1936. In both photos, the boys in top hats aren't wearing tailcoats, but rather a short coat for younger boys called an "Eton (whether or not the wearer was actually a student at Eton, e.g. the boys in "Toughs and toffs" were Harrovians) jacket." They are also wearing the wider, stiffer collars, called "Eton collars," which were part of the uniform for younger students. A student would upgrade to full morning dress as an older teenager, i.e. once he was closer to his full height (which is why it is inappropriate for children in wedding parties to wear the same clothes as adults). It is important to acknowledge that the three boys not in uniforms repudiated the photo as not representative of their realities – when interviewed, they pointed out that one reason they were dressed so informally was that they were playing hooky from their private Church of England school. Today, these schools have mostly relaxed their dress codes, but they — like Oxford — still have events where students must wear formal dress, thereby acclimating them to it. In my experience, youth orchestras serve a similar purpose in the US, albeit for evening dress rather than morning dress.

Originally, the morning coat, i.e. the cutaway tailcoat, was the informal option to the formal frock coat. Unlike the morning coat, which was a British invention, the frock coat has its roots in ancien régime French court dress.

For formal morning dress, the main choice is between the tailcoat or the frock coat as the trousers, shirt, waistcoat, tie/cravat, and hat requirements remain the same. Black is pretty much the only colour for frock coats. The frock coat style and cut is common among women's overcoats, and as a result the female version has more colour variations than the male version. Up until the 1980s, the frock coat was required dress for people working in the City of London.

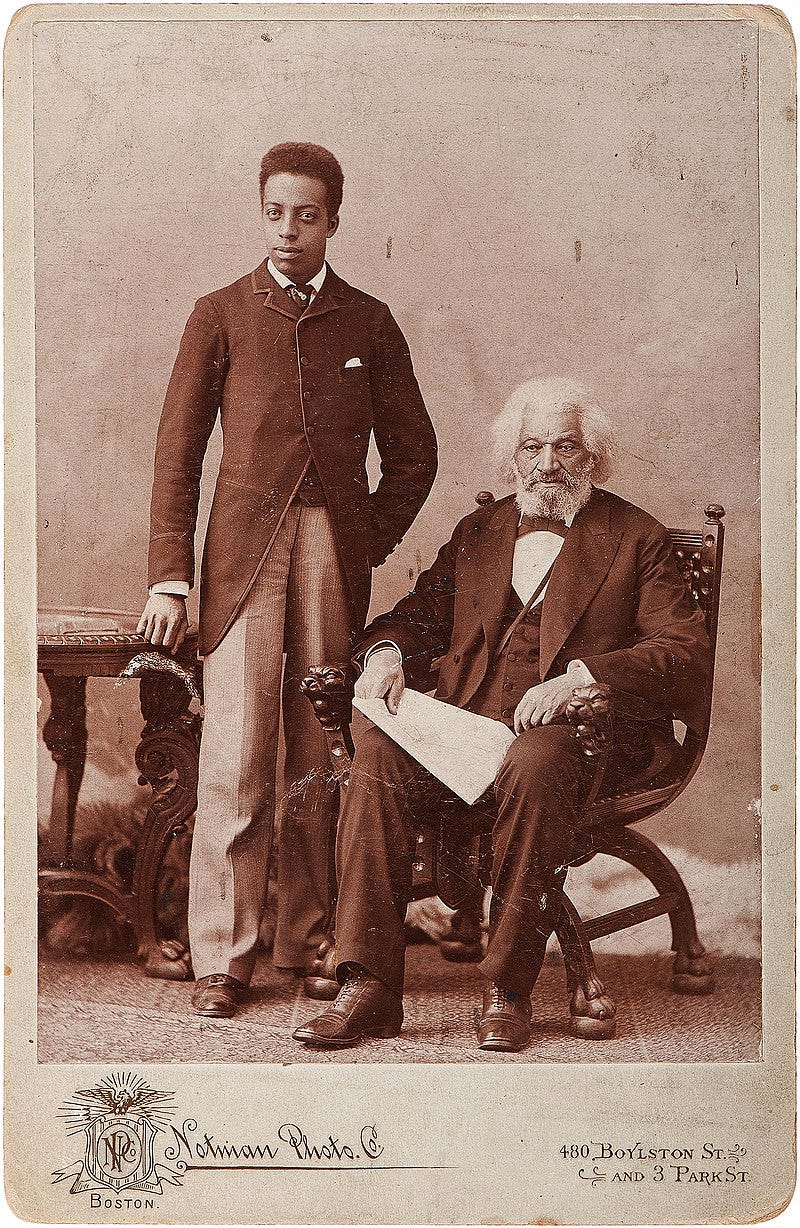

Here is a charming photo that captures the generational difference between a morning coat and a frock coat. Joseph Douglass, a concert violinist who studied at Boston Conservatory, was eighteen or nineteen in this photo. He wears full morning dress with a cutaway tailcoat. His grandfather, former slave and famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass, was seventy-three or seventy-four in this photo. He wears a frock coat with plain black trousers. Basically what Frederick Douglass is wearing would have been full formal daytime dress when he was a young man. The black frock coat is mostly not in use anymore, except in diplomatic circles where it is still formal dress for diplomats. It is also appropriate for state occasions, but the last one where the frock coat was widely used was Winston Churchill's funeral. It used to be required for daytime meetings with British royalty, but Edward VIII (the one who abdicated) suspended that protocol and it wasn't resumed after World War II.

Today, morning dress is the daytime equivalent of white tie. For women, the code is a dress that comes to at least the knee, but not to the ankle or ground, in a daytime colour (brilliant or vibrant colours are for evening) or pattern and a hat. If she wants to wear trousers, they should be ankle-length, black, and in a formal cut. Women's tops and jackets are held to the same rules as dresses in terms of colours or patterns.

The black tie, i.e. semi-formal, equivalent of morning dress is the stroller jacket.

A stroller jacket cut is similar to that of a lounge jacket, or what is now known as a suit jacket, but it is longer. It is meant to be worn with a lounge tie or bow tie, not a cravat. It is not paired with a top hat. The hat shown is a bowler hat. But the trousers, shirt, and waistcoat requirement remain the same as morning suits. When Winston Churchill made the V sign outside Downing Street during World War II, he was wearing a stroller suit paired with (I think) an Astor hat.

Ronald Reagan wore a stroller suit for his first inauguration, though not for his second. Conductor and pianist Daniel Barenboim appears to have worn a stroller jacket, trousers, shirt and tie at a concert at the Musikverein in Vienna in 2008. He does not appear to have worn a waistcoat — which might be uncomfortable for conducting — but that would mean that his outfit wasn't a proper stroller suit. Despite falling out of mainstream use (I believe law clerks in the UK are still required to wear strollers, but I haven't been able to verify that), stroller suits can still be purchased. I don't know of many situations where the stroller is worn, though, as most formal daytime events are assumed to require morning suits. Women don't really have an equivalent to the stroller suit. On the rare occasions where I have seen it used, for example by porters in Oxford, women simply wear the same suit as men.

The most regularly scheduled event where one must wear morning dress is Royal Ascot. The stewards will only admit people dressed according to protocol. There is a (probably) apocryphal story that stewards barred Princess Anne's daughter Zara when she showed up not dressed to code. Other formal events where morning dress is appropriate are weddings, christenings, or royal audiences. Otherwise, morning dress is expected at any occasion before 6:00 PM where the hosts specify the dress code is formal. Usually, this means weddings. At formal weddings, morning dress is not reserved for the bridal party, but it applies to all family and guests.

(The significance behind a Russian-Austrian [though raised in the US] Galitzine-Habsburg princess' marriage to a Roman Catholic commoner in a Russian Orthodox ceremony is a subject for another day. But if anyone is interested, an issue I wrote on the matter of aristocratic marriages, familial associations, and religious affiliation is linked here.)

However, there are reasons for not maintaining a formal dress code at a formal event, e.g. a wedding, which is by its nature meant to be a formal event. In my own family, we decided to have an informal dress code — lounge suits — for a wedding. We made this decision out of consideration for the fact that we were having a Tridentine Catholic ceremony, which meant we already had to enforce modesty standards as well as a religious dress code governing head coverings. Having to arrange these two aspects was challenging enough without adding in the complexities of morning dress. Her family did things properly and came attired in a combination of traditional dress — hanbok — and an East Asian variant of morning dress (I'm not sure of the Korean name, but in Japan, a similar outfit, rooted in the stroller suit, is called citydress).

On the subject of formal wear and weddings, something should be said about dress codes for cross-cultural formal weddings. The rule is that the women may choose to wear the traditional formal dress of their culture, but men should wear morning dress, with the exception of the groom, who may also choose to wear traditional dress.

I recently became aware after some events where this rule was followed that outside observers accused guests or participants of "cultural appropriation." This type of accusation is especially painful for multi-racial, multi-heritage people, such as a girl used to to know who had a Korean grandparent and was natively bilingual between Korean and English, but physically she took after the Caucasian side of her family, having blond hair and grey eyes. I would like to point out that accusing her and people like her of cultural appropriation is a form of racism perpetrated by people who often claim to be antiracists. In the meantime, my reaction is that anyone who thinks lounge suits are the apex of formal dress doesn't have the right to an opinion on clothes, culture, or etiquette.

On the final point of daytime formal dress, there is one institution whose sartorial and socio-cultural ignorance is legendary: Hollywood. If a scene involves formalwear, be it morning or evening dress, they will get something wrong. Here they made a particularly egregious mistake because it is specifically forbidden in sartorial etiquette books.

What's wrong with James Bond's morning suit? Hint: the problem is discussed above.

Answer: ˙ʇɐoɔ ƃuᴉuɹoɯ ʎǝɹƃ ʇɥƃᴉl ɐ ɥʇᴉʍ ɹɐlloɔ ƃuᴉʍ ɐ ƃuᴉɹɐǝʍ s,ǝH

Happy Sunday!

MLD